The Tragic Romance of Rejection

by Cynthia Levinson

Rejections? Let me count the ways. Not just the number, but the ways. When you’re a nonfiction writer, rejection comes in many forms as well as at many times.

I won’t even go into my first picture book manuscript, Mr. Bellow Lost His Cello, which won a national contest for unpublished picture books, was considered, revised, and rejected by two different editors at one of my most revered publishing houses, and was summarily rejected by a dozen others as well. (Okay, I did go into it. It’s hard to forget your first love, especially when it turns into a romantic farce.)

Leap-frogging over the subsequent umpty-ump picture book rejections, the next biggie, a middle-grade mystery novel wrapped around a multicultural search for identity, didn’t even make it to a publisher’s desk before being shot down. I took The Secrets You Tell (I’m still enamored of the title; maybe I can reuse it) to a week-long, by-application-only, whole-novel workshop. My assigned mentor’s highest compliment read, “It’s not the worst manuscript here.” The second-in-command trashed it. Skewered it. Demolished it. Trampled on it. (How many synonyms can I come up with?) It wasn’t only the worst manuscript there; apparently, it was one of the worst ever written. His critique was so thoroughly dismissive that I concluded that he had his own unresolved multicultural identity issues.

But it was also galvanizing. On the second day of the novel-writing workshop, I decided to stop writing fiction—and switch to nonfiction. His rejection, fortuitously but not intentionally, turned out to be exactly what my writing career and I needed. Thank you, _________.

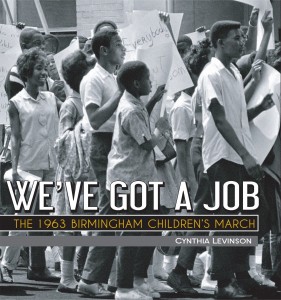

That doesn’t mean that rejections stopped flowing. My debut middle-grade nonfiction book, We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March, received nineteen rejects from eighteen publishers. (Yes, as with Mr. Bellow, two different editors at the same house sent it back.) And it wasn’t even a complete manuscript; it was merely four sample chapters, a fifteen-page outline, an annotated bibliography, and a tally of photo fees. Many editors saw what wasn’t ever going to be there in what wasn’t even there yet, until Peachtree Publishers saw what could be there–my editor taught me how to think about, research, organize, write, and edit a book.

That doesn’t mean that rejections stopped flowing. My debut middle-grade nonfiction book, We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March, received nineteen rejects from eighteen publishers. (Yes, as with Mr. Bellow, two different editors at the same house sent it back.) And it wasn’t even a complete manuscript; it was merely four sample chapters, a fifteen-page outline, an annotated bibliography, and a tally of photo fees. Many editors saw what wasn’t ever going to be there in what wasn’t even there yet, until Peachtree Publishers saw what could be there–my editor taught me how to think about, research, organize, write, and edit a book.

But it was in researching and writing this book and its successor, Watch Out for Flying Kids, that other forms of rejection walloped me—forms that are particular to nonfiction or, at least, to books that rely on particular kinds of research. We’ve Got a Job follows four real kids as they protested civil rights abuses in Birmingham, Alabama. The four in the book, however, are not the original four I’d hoped to follow. At first, there were three of them plus I’ll-call-her-“Gertrude.”

Gertrude had agreed to allow me to interview her and her friends and family, take pictures, and look through her albums—just as I was doing with the other three. Except she stopped answering my calls. And my emails. And my entreaties through her friends. In other words, she rejected me. It was like Kiss and Don’t Tell.

Being spurned personally was even worse than having the book proposal turned down multiple times. Now, I had a publisher; I just didn’t have a subject to write about. It took me a year to get over my attachment to Gertrude and to court someone else. The lessons I learned from this rejection: Don’t get too attached. Cut your losses. There are plenty of fish in the sea.

So I was ready, if need be, to put these lessons into practice with Watch Out for Flying Kids, a middle-grade nonfiction that follows nine teenagers who are involved in two children’s circus programs. It turns out that Kiss-and-Don’t-Tell rejections contain a sub-category, which I call the They-Love-Me/They-Love-Me-Not Dosey-Doe.

Since there is no secondary literature on children’s circuses, almost all of the book (except for background information on Hezbollah, the founding of St. Louis, and trick horseback riding, among other oddities) is based on interviews. All nine kids and their parents signed Release Forms letting them know what was in store if they agreed to participate. I think of it as their accepting my invitation to the prom. Except sometimes they stood me up.

Like Gertrude, “Alice” went months without answering my emails, phone calls, and Facebook messages. “Harriet” agreed to a date by Facebook video but went shopping with friends instead. “Shirley” became monosyllabic. (Me: “Can you tell me how you learned to juggle five clubs while hula-hooping on a rolling globe?” Shirley: “Practice.”)

How dare they have lives of their own?! How dare they want to protect their privacy?! Our book was at stake! The lesson I learned from Watch Out for Flying Kids: Never write another book that relies solely on the willingness of busy teenagers (some of whom speak languages I don’t) to be interviewed.

Actually, I think the solution to my rejection love life woes is to write fiction instead. Novelists don’t get rejected, do they?

Cynthia Levinson writes nonfiction for young readers. Her debut middle-grade book, We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March (Peachtree Publishers, 2012), won numerous awards, including the IRA Young Adult Nonfiction Award, Jane Addams Book Award for Older Children, YALSA Award for Excellence in Nonfiction (Finalist), American Library Association Notable Children’s Book, NCTE Orbis Pictus Outstanding Nonfiction for Children (Honor Book), and SCBWI Golden Kite Award for Nonfiction (Honor Book).

Cynthia Levinson writes nonfiction for young readers. Her debut middle-grade book, We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March (Peachtree Publishers, 2012), won numerous awards, including the IRA Young Adult Nonfiction Award, Jane Addams Book Award for Older Children, YALSA Award for Excellence in Nonfiction (Finalist), American Library Association Notable Children’s Book, NCTE Orbis Pictus Outstanding Nonfiction for Children (Honor Book), and SCBWI Golden Kite Award for Nonfiction (Honor Book).